Salman Rushdie and The Satanic Verses: what kind of idea are you?

The lie at the heart of the biggest free speech outrage ever

On Thursday I listened to the Origin Story podcast on The Rushdie Affair.

I wholeheartedly recommend it. People say a lot of horrifically stupid things about Rushdie and his famous book, but I have vetted this podcast and can attest that it is refreshingly free of all of them. (At least on the part of the hosts; they of course talk about the stupid things other people have said, and apply suitable levels of disgusted opprobrium.)

Here I want to discuss one aspect of this story that many people get wrong. In this case “many” may total several million. Such is the scope of the stupidity of this whole tragic mess. The podcast is solid on this point, but it bears emphasising nonetheless.

First, some background. Salman Rushdie is a novelist. His reputation as a master of post-colonial literature was established in 1981 with his second novel, Midnight’s Children. In 1988 he published his fourth novel, The Satanic Verses, and all hell broke loose. The novel was labeled an insult to Islam, and in rapid succession there were book burnings in the UK, deadly riots in Pakistan, the novel was banned first in India and then in other countries, and on February 14 1989 Iran's Ayatollah Khomeini delivered history's cruelest Valentine: a fatwa calling for Rushdie's death. Rushdie went into hiding for many years, before emerging to spend two decades as a walking, talking, publishing, partying global icon of free speech — until he was stabbed within millimetres of death in 2022.

I was a teenager when The Satanic Verses was published. I read it several years later, just after finishing high school, when I was hungry for the exhilarating oddities of modern literary fiction. I had studied Animal Farm at school; I knew how to spot some historical parallels and note down a few overarching themes; how hard could this be?

It was too hard for me. By the end, my joke for anyone who asked, was, “Now I want to kill him!” Thankfully no-one asked, and I'm glad I lacked a platform to publish my childishly sick attempts at humour.

Even if I had, I would have been swept away by the competition. I had the excuse of youthful insensitivity. There were hordes of mature, wise, erudite one-time defenders of freedom and civilisation, with no such excuse, who were eager to declare that Rushdie deserved what he got. They argued that as a Muslim he knew what he was getting into, and if the world of Islam condemned him to murder, well, hey, who were we in the West to presume to disagree?

One thing I find darkly fascinating about this story is that many of these people really were mature, wise, erudite one-time defenders of freedom and civilisation. How did they slip so spectacularly? Was this really such a moral banana skin? I have no answer — but it's worth remembering every time a crowd of opinion writers wade into the latest controversy.

History is kinder to Rushdie's defenders. The most entertaining was of course the inimitable Christopher Hitchens, who described the fatwa as the action of “a senile theocratic dictator who'd run his own country into beggary and bankruptcy and misery”. That line comes from a clip of Hitchens' turn on BBC Question Time to defend Rushdie being given a knighthood, and is an ideal place to hear the best and strongest argument in favour of the Satanic Verses, as well as the limpest hand-wringing criticism of it. Also, for good measure, a cringe-fest of irrelevant gibbering from a younger incarnation of Boris Johnson.

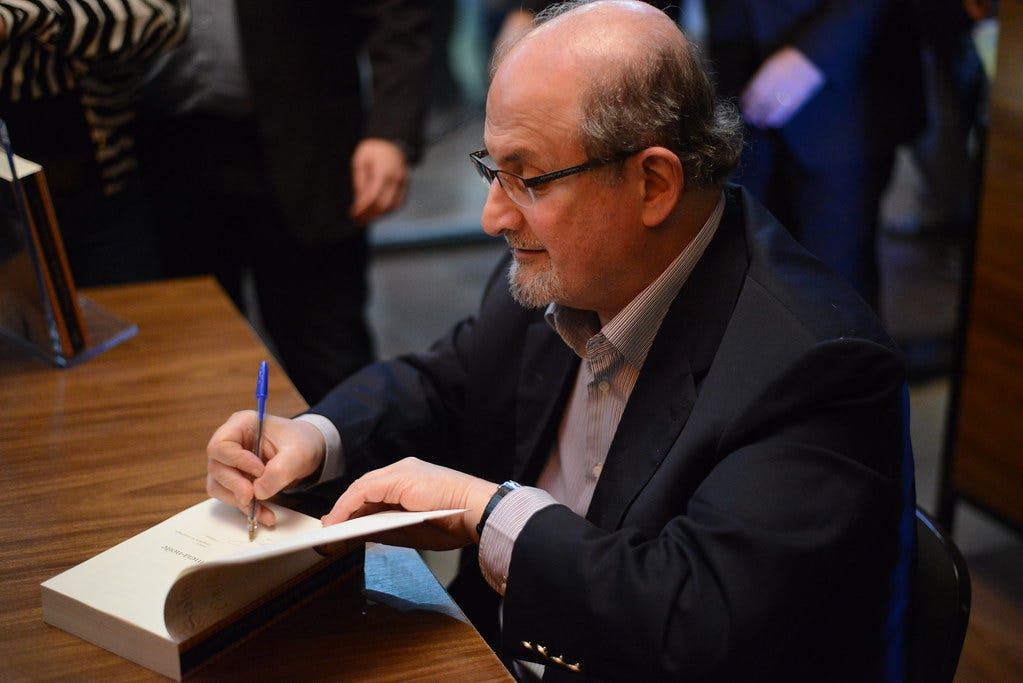

Years later, I decided to re-read the book after seeing Rushdie at the Hay Festival in 2011, and reading his incredible memoir of the fatwa experience, Joseph Anton1. (I tried writing an article about it at the time, and I was horrified today to discover this line in the draft: after bubbling at great length about what a lively, funny, relaxed speaker Rushdie was, a pure delight on stage, I wrote, “The days had long passed when he feared that an innocently foppish Hay attendee would draw a knife from his cravat and charge.” Jesus fucking Christ.)

Ok, now we get to the point I want to make. This point comes from having done what the many millions of fuming anti-Rushdie fulminators refused to do: read the actual book.

There are two parts to this, and I'm not sure which is more sickening.

The first is that this is, without any possibility of a hint of a doubt, a work of art. You may not like it (my younger self apparently did not), but there is no way that it is intended as anything but a massive, sprawling, digressive, insanely imaginative and bizarrely fantastical burrowing into all manner of depths of human experience. It is preposterous, indeed impossible while actually reading it, to imagine it as a pamphlet or a religious statement or an act of incitement. To attempt to hold in your mind the knowledge of death threats, riots, book burnings, and its overnight insertion into the highest levels of international political diplomacy, while reading this wild, exuberant, virtuosic testament to the human imagination, is the most bizarrely vertiginous experience.

Is this really the book that people got so upset about? How is this possible? The answer of course is that, as Hitchens put it (from the clip above, and quoted on the podcast), these are people “who not only haven't read this book, but couldn't read it”. He means it as an insult — and one that is fully deserved — but it's a statement that applies to most of the population. Hardly anyone reads novels, and even the people who pick up the occasional John Grisham or Dick Francis (as extolled by the execrable Johnson) would not make it two pages into The Satanic Verses. Even if Rushdie was planning to take the Prophet to pieces, he had reason to be supremely confident that no-one beyond a few harmless aesthetes would ever notice.

Which brings us to the second point, and this is almost wilfully ignored even by many of Rushdie's defenders: there is no insult!

Before you start hyperventilating over my presumption to tell people when they are allowed to be offended, a word of explanation2. The podcast describes very well how the upset over the novel began with people who read excerpts, out of context, and in translation. From then on it was a point of pride among his enemies to not read the book.

The most supposedly contentious part of the book — and only one part, among others that include two Indian actors falling from a plane that's been bombed by terrorists and miraculously surviving, an immigrant London disco where people dance to melting waxwork effigies of Margaret Thatcher, some late parallels with Othello, one woman who leads her village on a pilgrimage while shrouded in butterflies, and another woman who dreams of ships sailing through her living room — the contentious part is a dream sequence and/or delirium of a film star imagining himself in the lead roles of a fictionalised retelling of the birth of a religion.

We know what religion is being referred to here, but you may be surprised to hear that it comes out pretty well. It is hardly a take-down3.

In fact, the point of the story, as I read it, was to ask a very interesting question: will this new religion make compromises to win followers and legitimacy, or will it stand firm to its strange new principles? Rushdie directly announces a theme: “What kind of idea are you?” This is a question that goes beyond one religion, and indeed beyond all religions, to any movement in history. Does an idea survive and grow through assimilation and compromise, or, sometimes, because of the very opposite, claiming validity through its absolute refusal to budge?

It is a bitter irony that Rushdie's detractors have strived so hard to tell us their answer to that question. In the intervening decades since the novel's publication, several of them murdered its Japanese translator. Others have flown aeroplanes into skyscrapers, and unfortunately in real life no-one survived the fall. Yet other literary critics took a break from hunting down Rushdie and murdered some French cartoonists instead. Eventually their knife found him as well. They understood that the trick to make your creed triumph is to be as ruthlessly inflexible and thin-skinned as possible. That is the kind of idea they are.

They acted in response to an insult that did not exist, and talk of it distorts any discussion of the “Rushdie Affair”. Especially in a time when arguments for “free speech” have been co-opted by the far right as a defence for bigotry and, yes, insults. True free speech defenders and campaigners, and Salman Rushdie is one of their greatest, are not asking for the right just to degrade and belittle people. Yes, a free society includes mockery and ridicule — you are free to be a jerk — but it includes much, much more. To focus on insults is to get it entirely wrong. The free expression at the heart of the greatest free speech debate is pure, glorious, harmless art. There is no insult.

It is important for us to get that story straight. The fatwa story inspires a lot of talk about freedom of expression and freedom to question; we're told that they are foundational principles of our civilisation. I would certainly like to think so. And in their close company is a fastidious devotion to facts and honesty. That, I hope, is the kind of idea we are.

Readers may also be asking, “What kind of idea are you?” about this publication. Some science and academia, some fiction and… literary controversy? All I can answer is that if I am concerned with fiction and literature, and with science and truth, and with the necessary conditions for those to flourish, then this is a story that floods through all of them. Share and enjoy!

Here’s my older self’s reading list of Rushdie books: almost all of them. If you want the top few: Midnight’s Children is the masterpiece (they can’t stop trying to give it another Booker prize). The book I enjoyed the most and found the most beautiful was Enchantress of Florence. Joseph Anton is fascinating on his life in hiding. I am still steeling myself to read his new memoir, Knife.

On the insidious business of telling people that you didn’t mean to offend them, there is an illuminating story in Rushdie’s Languages of Truth, where he discusses British anti-semitism with Philip Roth. (Oh to have been there!) I won’t spoil it for you here.

I would be interested to hear from any avid reader of literary fiction, who read the entire book, and was offended, to explain to me why I am wrong. But perhaps not if they also think their offence justifies murder.

Great commentary.

Oh yeah, lots of insane things, and this was over decades, but so much more while he remained in hiding. Let's also not forget how annoyed the British public were about their taxes being used to protect a man they didn't care about.

Rushdie copped a lot of blow back when he finally got back to his life, new wife, parties, guest appearances? Good grief, who did he think he was? So much bile, so little sympathy, and so much ignorance - why bother understanding the bigger picture, the horror of it all and the lives affected.

Time has put a soft focus on a lot that happened, blurry, in fact. While it was happening, it was clear and ugly.

I have to admit I got a kick out of seeing Rushdie pop up in films and TV shows. It was good to see him having a lark. Who could begrudge him?

I have Knife in my reading pile, along with Joseph Anton, and Midnight's Children.