(This is Part 3 of a series of articles about consciousness and free will. Part 1 set up the problem. Part 2 talked about Erik Hoel's new book. And now, finally: do we have free will after all?)

All right, let's get down to business. What is “the scientific case for free will”, as proposed by Erik Hoel, and what do I think of it?

Hoel sets it up with a lot of fiddly technical arguments about causation and emergence. A decade or two ago, when scientific dilettantes wanted to sound clever, “emergence” was a term they liked to throw around. (Now they've moved on to “machine learning”. Oh, how we have fallen!) The emergence idea is that new physical laws “emerge” as you move up in scale: from the laws of individual particle motions emerge the laws of thermodynamics, from the chemical reactions of molecules emerge the processes of biology, and so on. Associated with this Hoel brings up something called the “exclusion argument”: since all laws of science emerge out of laws on ever smaller scales, it is the most microscopic scale that is most fundamental. Once you know the rules for the quarks and leptons and the four fundamental forces (or whatever yet whackier fundamental entities you think exist below them, strings or whatnot), everything else follows. Therefore, it's the quarks and their friends that are the root cause of everything.

This is not a line of thinking that leads to free will. This road ends with every court of law convicting the initial conditions of the universe.

Hoel makes the reverse argument. This is where the fiddly technical stuff comes in. You define a way to measure the causal weight of events, so that given some outcome, you can assign a measure of importance to all the various events that lead to that outcome. In doing this, Hoel argues, you can show that events at larger scales have greater causal weight. I won't try to repeat this argument, partly because my mind is too sluggish, but also because the result is not especially surprising. If a ball smashes through a window, would we assign more causal weight to the individual atoms in the ball and the window, or to the macroscopic collections that constitute the entire ball and the entire window? I would vote for the latter. If you disagree, you can take it up with Chapter 10.

If we buy this, then the “exclusion argument” has turned upside down: for most phenomena, the cause-and-effect is all at the large scale of the phenomena itself, and we can ignore the fundamental particles. As I said, this is not surprising. Sure, you can always find some gibbering nerdish freak in the basement of a physics department who will argue that the ball smashed into the window because of quantum fluctuations in the early universe, but everyone else would say it was because some fool threw it.

It is no great leap to follow this argument to the conclusion that the vast bulk of the cause of a person's actions lies in the fiendishly complex fizzing and popping going on inside their brain. Of course there was some influence from their hectoring parents, or the taste of their tenth-birthday cake, or the gun currently pointed at their head, but all of that counts for little compared to the vast weight we have to assign to the deliberations of their conscious mind over the last five minutes.

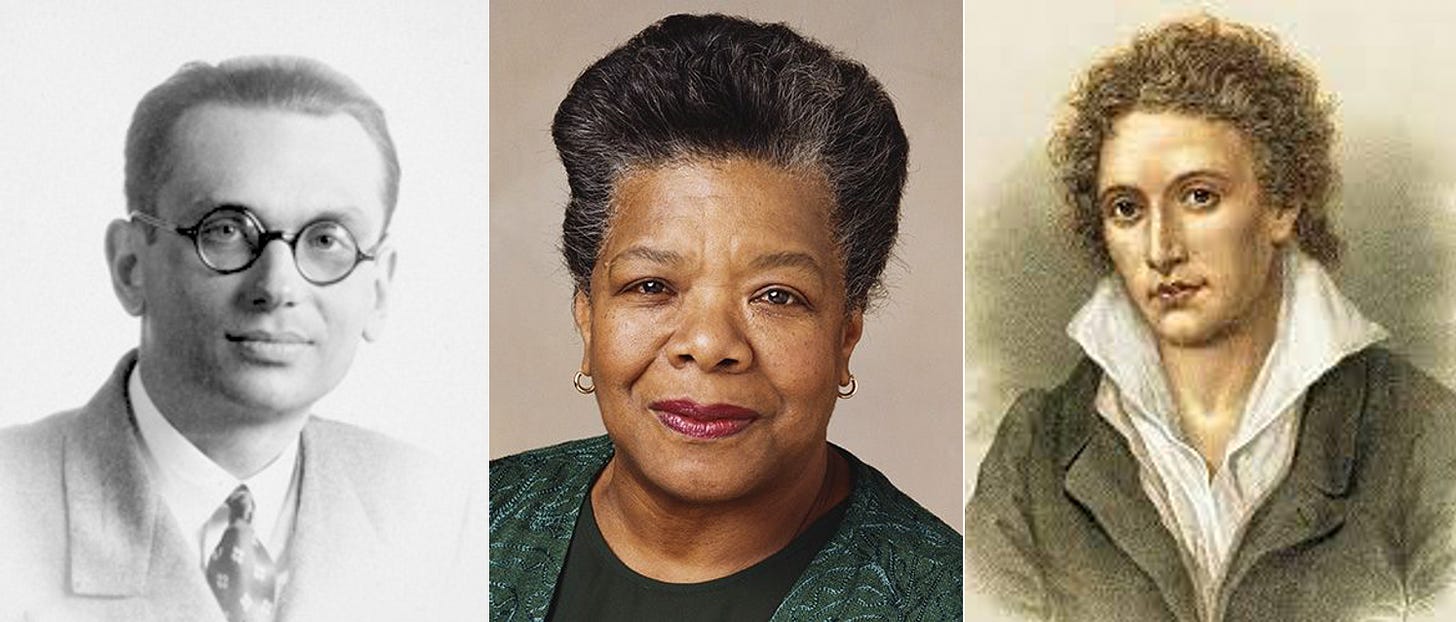

Thus — ta-da! — our minds are the main cause of our actions, and therefore we are responsible for our decisions. Free will is saved, and Hoel can end his book cartwheeling off into the sunset invoking Percy Shelley and Maya Angelou.

Before we get to criticisms of this argument, let's give it its due. It does tidy up the moral responsibility question. Yes, the killer was raised by a family of professional assassins and disgracefully mocked for their rigid dietary requirements, but ultimately it is they who are personally responsible for choking their boss with a cardboard straw.

If I've presented Hoel's conclusion as if it is simple and obvious, that was disingenuous. All great ideas seem obvious in retrospect, and although it's unclear how prominently causal emergence will sit in the final history of free will debates, this was certainly not an idea I had come across before. It does help clarify some discussions, and (at least in my own thinking) helped clear up many things.

That said, am I convinced? No. But I have been nudged more than by anything else I've read about free will in the last 30 years.

That we are the cause of our actions does not on its own make us free, any more than the ball is free because it caused the window to smash. Ok, sure, between input and output the brain goes through fantastically complicated processes. Yes, but so does the Earth's geology, and we do not say it possesses free will to decide the timing of earthquakes and volcanoes. One may object that the brain is different because it processes information. I'm not sure why that is so special (I've never been sold on the modern scientific deification of “information”), but, anyway, so does my computer.

And that brings us back to the crux of the matter: the key difference is consciousness. On this point I am with Hoel all the way.

Here is how I see his case for free will. My consciousness gives me the feeling that I am making independent decisions. The dominant cause of my actions is the output of my conscious brain, so my feeling is correct. What more free will could I ask for? In fact, if I prefer to exclude any possibility of “non-physical” effects (the spirit, the soul, and other such vagaries), what more free will could I ever hope for? Hoel even provides a bonus feature: it is entirely possible that it is fundamentally impossible to simulate and predict the output of a conscious brain, so I get to feel a vital bit of extra security that my future decisions are a mystery until I have made them.

You can decide for yourself whether you find that satisfying. (Ha ha! Free will joke!)

I am not convinced that this achieves what most people mean by free will. The brain is still deterministic (plus perhaps a few rolls of the quantum dice). Maybe you can't predict or determine the outcome, but so what? I would hardly call this being properly free. I would say that “properly free” does not make any sense in a material universe, and maybe Hoel would say “what are you complaining about?” and perhaps that is where we leave it.

Except for two points, one hopeful and one grim.

First, the grim one.

Hoel talks about scientific incompleteness, which is the extrapolation of specific technical results in mathematics (Goedel's incompleteness theorems) to all of science, with the result that some things are inherently, fundamentally unknowable. This and related ideas add up to an argument that it is impossible to simulate a human brain and predict its decisions.

This is wishful thinking. It is entirely possible that at some point in the future we understand the laws that operate in the brain, and we can simulate them to sufficient precision to accurately predict how people will behave. Even more terrifying, maybe we could determine precisely what inputs are necessary to fully manipulate the brain's decisions. The people who get a shiver down their spine when they read about micro-targeted election advertising may suspect that such a day is not far off — or already here.

If we can fully predict, for all practical purposes, what people will do, and we can effectively operate them by remote control, what consolation is causal emergence?

Now for the second point, which helps us off this dystopian ledge.

As noted in the first part of this series, our current ignorance works both ways. Central to “I survey my brain and I make a decision” is consciousness, and we have no idea how that works. We can't even define what it means! So we can still hope that when we do understand consciousness we will discover some clever mechanism that does give a much greater kind of freedom.

Sure, maybe. But at the moment we have to be honest that this is no more than a romantic hope: the explanation will just as likely scupper free will for good.

In the mean time, we are no further forward. We may be able to make a technical argument for why our decisions are our own, but they are still determined. If we want to fully explicate what that means, or hold out a slim hope that there is a way to sidestep determinism, then we still must resolve the mystery of consciousness. Eventually — eventually! — someone will crack it, but there are no tangible signs of progress.

It still sounds exciting, though. I wonder if it's too late for me to join in?

[Postscript: How to live in a world without free will.]

Hi Mark,

You touch upon predictability and chaos theory, and still show yourself unsatisfied with the notion that free will and conscioness ought to be more our inability to predict the actions of humans beings. Why is that? From your text, I can't really see where you see that falling short. From the discussion of quantum stuff to computability, you have clearly thought through this for while, hence my curiosity.

FWIW, I have written about all this a couple years ago (https://bonitao.medium.com/the-wanda-maximoff-illusion-68f513a0f49, and here is the paywall free version: https://bonitao.substack.com/p/the-wanda-maximoff-illusion-68f513a0f49). Not sure if my text has anything novel for you, but you may still find it interesting, if anything for its optimistic wrap up.

Would be curious to know your thoughts on why what we call conscious is not "what we feel cannot grasp how it could be predicted". Is it a more of a semantics opposition, or a philosophical one? Or maybe you just find the whole idea ludicrous?